Who Was Tappūtī?

Who was Tappūtī-bēlat-ekalle, and why am I writing about her?

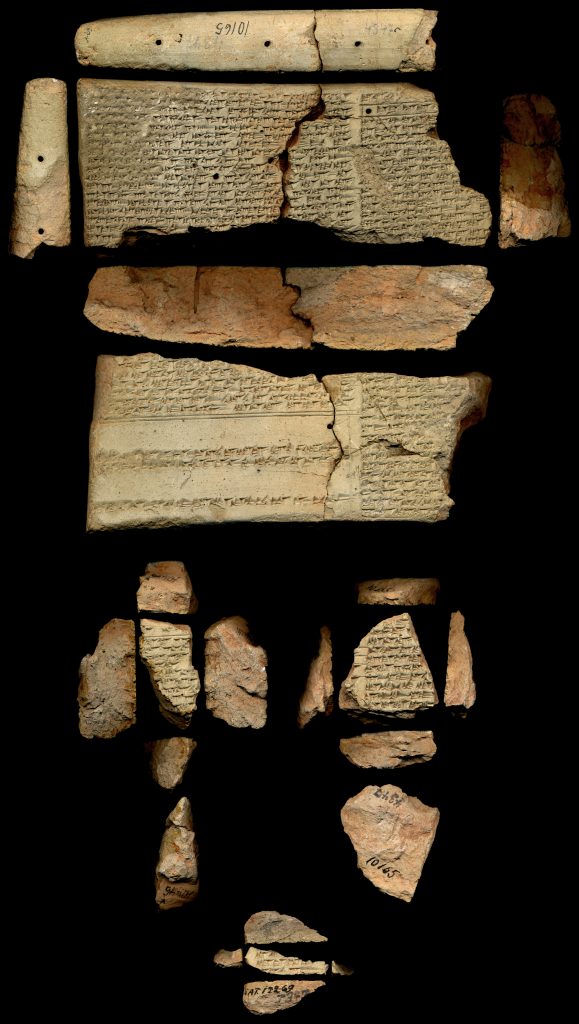

Tappūtī-bēlat-ekalle – ordinary woman or extraordinary scientist? Manual laborer or visionary artist? And so the questions begin about this 13th century BCE ancient Assyrian woman popularly and wrongly credited as “the world’s first perfumer”. What little we know of her is thanks to a recovered cuneiform tablet (found in modern day Iraq, written in Akkadian) naming Tappūtī as the reciter of a perfume recipe for a king. Let’s take a look at this tablet, currently housed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany.

WHAT HAS BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT TAPPŪTĪ?

Next, let’s visit historian Nuri McBride’s Death Scent for a critical overview of recent discussion about Tappūtī:

After following popular discussion about Tappūtī, Nuri begins:

If you Google Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim, you will find dozens of articles praising her as the first perfumer. Online, Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim is presented as a feminist, a scientist, and an entrepreneur. Yet, those concepts would have been utterly foreign to her lived experience. Images accompanying these stories feature Babylonian goddesses, Sumerian queens, and Urukian tablets. They’re a strange choice for stories about an Assyrian perfumer.[3]

I’m not sure I could write a better overview about Tappūtī. So much of what has been written about her over the last 5 years is, well, factually incorrect. Even Wikipedia is not quite accurate…

TAPPŪTĪ IN WIKIPEDIA

Here’s what Wikipedia has to say about Tappūtī:

Tapputi, also referred to as Tapputi-Belatekallim (“Belatekallim” refers to a female overseer of a palace),[1] is one of the world’s first recorded chemists, a perfume-maker mentioned in a cuneiform tablet dated around 1200 BC in Babylonian Mesopotamia.[2] She used flowers, oil, and calamus along with cyperus, myrrh, and balsam. She added water or other solvents then distilled and filtered several times.[3] This is also the oldest referenced still. She also was an overseer at the Royal Palace, and worked with a researcher named (—)-ninu (the first part of her name has been lost).[4] Tapputi used the first recorded still and wrote the first known treatise on perfume making, which is preserved on a clay tablet. She developed a technique using solvents in order to make scents lighter and longer lasting.[5][better source needed][4]

Well, that’s not quite accurate. For starters, we now have a better understanding that her name – “bēlat-ekalle” – was likely a direct reference to the goddess of the same name, also known as Ninegal, who was known as a protector of royal palaces. See Archi and Asher-Greve below for scholarly discussion.

- Archi, Alfonso (1990). “The Names of the Primeval Gods”. Orientalia. 59 (2). GBPress – Gregorian Biblical Press: 114–129. ISSN0030-5367. JSTOR43075881. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- Archi, Alfonso (2004). “Translation of Gods: Kumarpi, Enlil, Dagan/NISABA, Ḫalki”. Orientalia. 73 (4): 319–336. ISSN0030-5367. JSTOR430781731. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- Archi, Alfonso (2013). “The West Hurrian Pantheon and Its Background”. In Collins, B. J.; Michalowski, P. (eds.). Beyond Hatti: a tribute to Gary Beckman. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. ISBN978-1-937040-11-6. OCLC882106763.

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). Academic Press Fribourg. ISBN978-3-7278-1738-0.

WAS TAPPŪTĪ A DISTILLER?

Next, numerous scholars have debated that though the technology for distillation was likely in its infancy during the 13th century BCE, there is no evidence that Tappūtī or her contemporaries actually utilized this technology in their perfume-making processes. Middeke-Conlin explains:

Levey notes on page 31 that the pottery needed for distillation existed dating back to 3500 BC. Limet, however, does not see evidence for this in the texts. It can be stated, then, that while ceramic technology may have existed which allowed for the production of aromatic essences, there are no textual evidence for this ceramic technology’s application to such production.[5]

So, she was likely neither a head of a palace nor distiller. Moreover, there is no credible source that she utilized solvents as claimed by Wikipedia.

SO, WHO WAS TAPPŪTĪ?

We know the following:

- She was a woman who lived in ancient Ashur, though she may originally have come from somewhere else.

- She worked with natural materials (e.g. plants, spices, flowers, resins).

- She was likely in the employ of the palace of King Tukulti-Ninurta I.

- There is no historical evidence that she was a head perfumer, or even a master perfumer.

- She had basic knowledge of chemistry that allowed her to extract essential oils and resins from organic matter.

- She had knowledge of how to make fine oil, fit for a king, and so likely worked on products for the palace.

- There is no evidence she used distillation.

- She could have been able to read and write.

- She worked with at least one other perfumer per the evidence we have on KAR 220.

THE PERFUMER OF ASHUR

With the limited knowledge we have of Tappūtī, The Perfumer of Ashur attempts to create a life story for her. Author and historian Marlen Harrison utilizes cuneiform evidence from ancient Assyria, knowledge of Mesopotamian perfume-making processes, and scholarly discussion about this dynamic culture to create an epic new work of historical fiction.

CREDITS

[1] “Girl with Herbs.” Accessed May 24, 2025. Dall-E.

[2] “KAR 220.” Accessed May 24, 2025. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany, https://cdli.earth/collections/215.

[3] Mcbride, Nuri. “Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim: The First Perfumer?” Last updated December 7, 2012. https://deathscent.com/2022/07/12/tapputi-belatekallim/Death Scent.

[4] “Tapputi.” Accessed May 24, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tapputi.

[5] Middeke-Conlin, Robert. “The Scents of Larsa: A Study of the Aromatics Industry in an Old Babylonian Kingdom.” Cuneiform Digital Library Journal, 2014:1.

Learn more about The Perfumer of Ashur’s main character, Tapputi, here. Read about The Tapputi Project here. Learn more about the Assyrians here. Get to know the author here. View the KAR 220 tablet with Tappūtī’s pefume recipe for a king here.