What is The Tapputi Project?

How might a public historian develop an immersive digital or in-person exhibit that crafts an interpretive historical narrative about Tapputi?

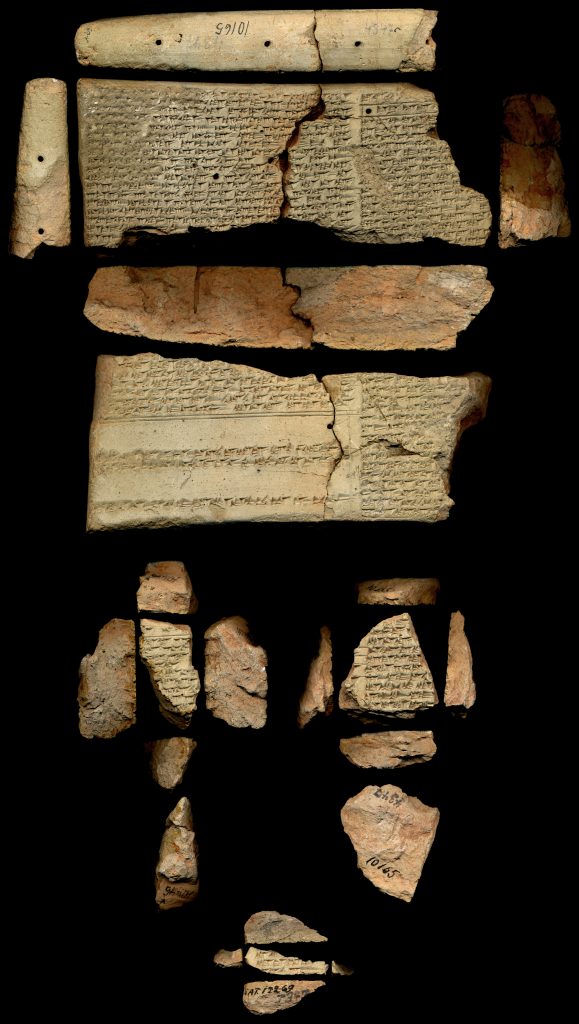

The earliest-dated written evidence of a named individual with the clear title of “perfumer” is found on a cuneiform tablet created ca. 1350 BCE in ancient Ashur, Assyria, or modern day Iraq. It is now housed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany (see figure 1). This by no means suggests this individual is the world’s first perfumer. Rather, the tablet presents the earliest written evidence we have of a named individual who is also indicated to be a perfumer, accompanied by an actual perfume recipe.

Figure 1. KAR 220 (P282617) Literary tablet excavated in Assur (mod. Qalat Sherqat), dated to the Middle Assyrian (ca. 1400-1000 BC) period and now kept in Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany. Image © Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany

The tablet language and translation is available to view on the ORACC, or Open Richly Annotated Corpus of Cuneiform website hosted by University of Pennsylvania. It describes a recipe and process for making a perfume for a king. This recipe is attributed to Tapputi, the King’s muraqqītu or previously mentioned “aromatics specialist.” This individual also possibly held the title Bellat-ekallim or “head of the palace household,” but this has been disputed and may in fact be bēlat-ekalle (see my post here).

The KAR 220 tablet was first translated by Ebeling into German in 1919. It was translated into English by Levey in 1954, and most recently updated in English by Escobar in 2020. In 2023, a team of Turkish researchers claimed to have re-visited the tablet to produce 27 pages of translation including information about Tapputi’s perfume-making process not present in either Levey’s or Escobar’s translations[2].

Historical Topic Defense

There is clearly public interest in perfumery and perfume culture with global perfume sales growing annually and projected to reach around USD 64.41 billion by 2030.[3] Additionally, there currently exists a popular trend in historical fiction of feminist re-tellings of legendary tales from classical studies[4]. As such, global audiences would seem to be open to learning about an ancient female perfumer.

Moreover, the KAR 220 tablet (the only evidence of Tapputi’s perfume-making process and recipe) was given an English language update in 2020 by Escobar. In 2022, a Turkish research group (as noted above) researched and developed Tapputi’s perfumes as retail products available for purchase and use. And just last year, Levy’s 2023 MA History thesis proposed an immersive, sensory, scent-focused exhibit on first millennium BCE Assyrian medical practices and remedies[5]. Finally, there has been a growing contemporary focus on women and gender in Assyriology as evidenced by recent published scholarship[6].

The proposed scholarship will connect these three worlds – ancient Assyria, Tapputi the female perfumer, and olfaction/fragrance – in order to answer the following research questions.

Topic Interpretation

Questions

How do existing primary sources, specifically the KAR 220 tablet, and related secondary research – e.g. Halton & Svärd; Stol; Michel – construct Tapputi as a) an Assyrian, b) as a woman, c) as a “bellatekallim” or palace head, and d) as a perfumer? What does the historical record offer us in way of evidence as to how Tapputi’s fragrance was created and used? How might a public historian develop an immersive digital or in-person exhibit that crafts an interpretive historical narrative about Tapputi?

Conclusions & Contribution

The KAR 220 tablet will offer information about:

- Assyrian court and perfume cultures,

- evidence of high-ranking women in the court of Tukulti Ninurta I,

- information about Tapputi’s status and role at the palace,

- and information about what may have been used in perfume recipes and their methods and apparatuses of creation.

This knowledge has been previously interpreted, as noted above (e.g. Ebeling, Levey, Escobar, Turkish group), from the perspective of overall translation for meaning and the identification of the perfume materials themselves.

This scholarship seeks to develop a more nuanced and multi-dimensional portrait of Tapputi as an individual. Who was Tapputi the Assyrian, the female scientist, the perfumer? This early research will inform creative projects such as a work of historical fiction about Tapputi and her craft, and related multimodal sensory public history exhibitions of her story and work.

Challenges

I am working with a cuneiform tablet composed in Akkadian, approximately 1350 BCE. This tablet was initially transliterated into German (1910), later translated into English, (1960) and then transliterated again 60 years later (into English, 2020). As such, the ideas presented on the tablet have been touched by at least three people attempting to make meaning.

The most recent English transliteration has taken into consideration its forerunners as well as nearly 100 years of Assyriological scholarship. In terms of working with translations of texts and the noted secondary sources, I align myself with Raign:

Although none of these translations was published in a critical edition, each was translated by an expert and published in a scholarly book, journal, or corpus. My choice of translation does not eliminate the potential for varying or incorrect translations, but the benefits of analyzing the rich trove of recovered texts outweighs concerns regarding the particular translations themselves.[7]

This position may change as I work through the project should I find major discrepancies or biases in translations.

Professional standards

I can follow and respect the values set forth in section 3 of the AHA statement on scholarship, for example:

Professional integrity in the practice of history requires awareness of one’s own biases and a readiness to follow sound method and analysis wherever they may lead. Historians should document their findings and be prepared to make available their sources, evidence, and data, including any documentation they develop through interviews.

Likewise, Historians should not misrepresent their sources. They should report their findings as accurately as possible and not omit evidence that runs counter to their own interpretation. Historians should not commit plagiarism. They should oppose false or erroneous use of evidence, along with any efforts to ignore or conceal such false or erroneous use.

Historians should also acknowledge the receipt of any financial support, sponsorship, or unique privileges (including special access to research material) related to their research, especially when such privileges could bias their research findings. They should always acknowledge assistance received from colleagues, students, research assistants, and others, and give due credit to collaborators.[8]

I can use this as a guide or checklist for ethics and sound practices. I will make sure to document accurately all sources, to not omit evidence, and to acknowledge any assistance received.

Research Methods

I will undertake archival research using the primary document KAR 220 as shown above, and its translations by Ebeling, Levey, and Escobar. As noted earlier, strengths of this earlier research include transliteration and translation of the tablet with some analysis and interpretation explaining the perfume-making process as dictated by Tapputi. Weaknesses include a lack of attention to more deeply discussing who this individual was as a perfumer, as a woman, and why she did what she did. As such, there is much room for additional analysis and narrative construction in order to create a fuller picture of Tapputi.

Additional primary documents will be considered as translated and discussed by their authors as addressed below. Secondary sources will be used to supplement the KAR 220 translation; these contain translations and discussions of numerous primary texts.

In terms of working with translations of texts and the noted secondary sources, again I align myself with Raign as previously noted above.[9]

Secondary Source Analysis

There has been no specific academic treatment of Tapputi Bellat-Ekallim as of the time of this writing. Existing scholarship examines her perfume-making processes and recipes, but questions remain as to her life path and circumstances. Much social research has been undertaken throughout the last 30 years that puts women and gender as a focus of inquiry. As such, I will be utilizing existing scholarship to support my cultural historical approach, as my ultimate goal is to craft a narrative about Tapputi that is grounded in the historical record and research, rather than to problematize the translations themselves.

1) Bottéro, Jean, André Finet, Bertrand Lafont, Georges Roux, and Antonia Nevill. Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Edinburgh University Press, 2001. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1r258j.

Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia is a collection of articles originally published in the French journal L’Histoire by Jean Bottéro, André Finet, Bertrand Lafont, and Georges Roux. The book presents a snapshot of thinking from throughout the 1990s by leading French Assyriology scholars. As such, the work is not an exhaustive account but deep dives into each of these scholars’ own specialized agendas. The book is divided into multiple chapters individually authored by one of these four men and translated into English by Anotnia Nevill.

A good part of the text is dedicated to discussion of women in ancient Mesopotamia. For example, Jean Bottero discusses feminist issues in a culture where women generally were owned by men in Chapter 7: ‘Women’s rights’, while Finet discusses a royal harem in Chapter 8: ‘The women of the palace at Mari’. And Georges Roux investigates ‘Semiramis: the builder of Babylon’ in Chapter 9. The authors offer lively interpretations based on their considerable research experience.

Authors rely on foundational readings (transliterations) of key texts, but no citations or notes are presented to help us understand the origins of conclusions. Accordingly, no bibliography is included. This seriously limits this writer’s ability to trace the origins of ideas and corroborate them by identifying the textual evidence behind such assertions.

2) Chavalas, Mark W. 2014. Women in the Ancient Near East : A Sourcebook. Hoboken, London: Taylor and Francis ; Routledge.

Women in the Ancient Near East: A Sourcebook is one of the first full-length treatments of Mesopotamian women’s lives (2014). Intended to provide an introduction and overview of women in the Ancient Near East(ANE), it is a supplemental textbook for those studying women’s or ancient Near Eastern history. The book provides both the primary sources alongside new translations and commentary, filling a void in women’s and in ancient Near Eastern historical studies.

However, limitations or criticisms include a lack of consideration of non-textual evidence (e.g. material or iconographic), and at least a few of the chapters employ questionable or outdated scholarship. In terms of scholarship, authors typically rely on foundational readings of key texts rather than engaging with these original sources as primary sources; strong documentation and citation aids credibility here. This book will be helpful at filling in the picture of Tapputi as a Mesopotamian woman while emphasizing the relationship between ideas about women and textuality.

3) Stol, Marten. Women in the Ancient Near East. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2016.

Marten Stol’s Vrouwen van Babylon published in Dutch in 2012 was fortunately translated into English and published in 2016 by de Gruyter as Women in the Ancient Near East, and stands as one of the only full-length treatments (nearly 700 pages) in English about women of this time and place, and currently available via open access. Women in the Ancient Near East marks a continuance of his earlier interests and contains thirty-two chapters that attempt to present a holistic overview of the lives of women in this geographic region (ancient Mesopotamia) from as early as 3100 BC.

Stol’s sources are wide and varied, drawing from linguistic as well as sociocultural studies across an array of languages, disciplines, and time periods. However, at times the reader wonders how strongly the author considered contemporary studies and reinterpretations in light of his conclusions drawn from older sources. For example, the concept of the harem has regularly and widely been debated, and alternative terms have been suggested such as “royal women’s quarters.”[10] This issue of language and interpretation could have been addressed in greater depth as one way of critiquing knowledge production about women and helping readers understand the multiple perspectives on such topics.

4) Lion, Brigitte and Michel, Cécile. The Role of Women in Work and Society in the Ancient Near East. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2016.

Edited and overseen by French and Japanese Assyriologists, this multi-author anthology was one of the first volumes dedicated specifically to focus on women’s involvement in economic life in the Ancient Near East, and one of the first to be overseen by and to so heavily feature female scholars.

One of the great strengths of the book is that it presents its scholarship in chronological order, allowing the reader to consider how some of these issues developed over time. Additionally, it underscores that ANE women could be economic agents, both inside and outside the family structure. Authors typically rely on foundational readings of key texts with consistent documentation and citation.

This book will offer opportunities to consider Tapputi in terms of her industry and earnings, perhaps shedding light on her professional status as palace head.

5) Halton, Charles, and Saana Svärd, eds. Women’s Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Anthology of the Earliest Female Authors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

The first volume specifically about women writers in Mesopotamia, Women’s Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia narrows the focus from women in general to a specific action – literacy. Offering contemporary translations of works composed or edited by female writers as well as elite women of the ANE, these “letters” and their translations and discussions provide insights into social status, conflict, and success of women during 2300–540 BCE.

The translations cover a range of genres, including hymns, poems, prayers, letters, inscriptions, and oracles. Each text is accompanied by a short introduction that situates the composition within its ancient environment and explores what it reveals about the lives of women within the ancient world, and original texts and translations are clearly noted for every passage. Questions about women’s agency, authority, and power are addressed.

6) Radner, Karen and Robson, Eleanor. The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. London: Oxford University Press, 2020.

The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture examines the ANE through the lens of cuneiform writing. The authors here are scholars from numerous disciplines. Strengths of the book are that its authors both examine and look beyond the boundaries of the written word, using tablets not just as ‘texts’ but as ‘material artefacts’ that can provide important information about their creators, readers, users and owners.

The writing is well-cited, employing a blend of foundational scholarship with contemporary research. Of significance to the current proposal is the attention paid to the lives of women as well as the presence of female scholars. One limitation, and indeed a criticism by reviewers, is the premise of viewing all cuneiform culture homogenously despite the wide variety of language, both textual and logographic, used to create it.

7) Michel, Cécile. Women of Assur and Kanesh: Texts from the Archives of Assyrian Merchants. The Society of Biblical Literature, 2020.

Michel’s 2020 monograph is described as the first definitive account of the everyday lives of women from ancient Mesopotamia. As such, one of its strengths is its exhaustive coverage of women’s roles through the use of over 300 primary texts and the benefit of its author’s 30+ years of scholarship specifically on the topic of Assyrian merchants. The indexes of names, concepts, locations, etc. are especially helpful in providing additional context and explanation to the primary source translations and make this a stronger resource for learning about women of the ANE than many of the other books annotated here.

Michel’s work is enormously helpful in developing a more well-rounded view of Tapputi. Focusing on the wives, mothers and daughters of merchants, offers intriguing portraits of social, economic, and domestic activities, financial realities, family affairs, and everyday worries. This work illustrates that many women were indeed literate and quite industrious.

8) Veenhof, Klaas R. “Ancient Assur: The City, Its Traders, and Its Commercial Network.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 53, no. 1/2 (2010): 39–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25651212.

Veenhof’s 2010 article about the development of Assur as a city and its trade practices offers much in the way of understanding who Tapputi might have been as a citizen, as well as understanding its inhabitants. Veenhof, an established and well-published Dutch Assyriologist and professor emeritus at University of Leiden, begins with a description of the commercial role of Assur and its activities before moving to a discussion of the organization and status of its traders. This information is helpful in understanding how Tapputi may have obtained her perfumery materials as well as the influences on Assur and its cultural practices from outside players.

The scholarship is well referenced with additional notes throughout offering clarity or background. Veenhof concludes that a powerful merchant class also played an important role in Assur’s administration thanks to precious trade ties. The article paints an excellent picture of what kind of citizen Tapputi may have been as someone likely directly involved with trade of goods.

Primary Source Analysis

US LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COLLECTION

Minassian, Kirkor, Former Owner, and Kirkor Minassian Collection. Library of Congress African and Middle Eastern Division. loc.gov/collections/cuneiform-tablets/

The US Library of Congress’s collection titled Cuneiform Tablets: From the Reign of Gudea of Lagash to Shalmanassar III includes school tablets, accounting records, and commemorative inscriptions held by the United States Library of Congress featuring 38 cuneiform tablets accompanied by supplementary materials dated from the reign of Gudea of Lagash (2144-2124 BCE) to Shalmanassar III (858-824 BCE) during the New Assyrian Empire (884-612 BCE). The collection was acquired in 1929 from an art dealer, Kirkor Minassian.

Roughly half of the tablets have been identified as administrative records. And about a third of them are school exercise tablets used by scribes learning cuneiform. The remaining tablets are temple accounting records. The oldest tablets date from 2144-2124 BCE. There are also two brick fragments dated to 858-824 BCE.

Application

The tablets in this collection may offer insight and background to help us better understand the context of the primary sources listed below. For example, did Tapputi write her own recipe? If not, who did? What does this tell us about her? Is there anything about the language use in these documents that might shed light on the language used in the tablets below?

There are no current studies that specifically seek to construct an identity for a) Tapputi Bellat-ekallim, or b) perfumers of that time period. As such, considering primary source collections such as this one alongside the tablets below may help us to construct a more detailed understanding of who she was and what she did.

Limitations include the problem of time periods; all of these tablets in the Minassian collection are dated well before or after the Middles Assyrian period when Tapputi lived. However, they may still provide some helpful context where nothing else exists.

PRIMARY SOURCE CUNEIFORM TABLETS

- “KAR 220 Artifact Entry.” (2005) 2023. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). June 1, 2023. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P282617.

- “KAR 140 Artifact Entry.” 2005. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). November 11, 2005. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P282611.

- “KAR 222 Artifact Entry.” (2005) 2023. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). June 1, 2023. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P282618.

- “PKT Pl. 6-8 Artifact Entry.” (2005) 2023. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). June 1, 2023. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P282519.

- “PKT Pl. 9,1 Artifact Entry.” (2005) 2023. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). June 1, 2023. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P282520.

- “PKT Pl. 5 Artifact Entry.” (2005) 2023. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). June 1, 2023. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P282518.

There are no formal publications, archives, or collections that specifically focus on the current research questions about a 13th cent. BCE Mesopotamian perfumer: Who was Tapputi Bellat-ekallim, how did she become a perfumer, and what were her practices like? However, the earliest-dated written evidence of Tapputi, a named individual with the clear title of “perfumer” is found on a cuneiform tablet created ca. 1350 BCE in ancient Ashur, Assyria, or modern day Iraq. It is now housed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin, Germany).

The tablet language and translation, along with five others discovered at the same time in the same location, is available to view on the ORACC. The ORACC makes translations available in English alongside the transliterated cuneiform (into Akkadian, typically). When applicable updated transliterations or translations are also noted.

A Perfume Recipe from Tapputi

The fist tablet, KAR 220, describes a recipe and process for making a perfume for a king as dictated by Tapputi, the King’s muraqqītu or “aromatics specialist.” The other tablets, written in a similar style and method, also address perfume-making processes, but do not directly name Tapputi. One of the tablets attributes its recipe and process to a different female perfumer, but only part of the name survives, “-ninu.”

Limitations of these sources include the problem that as a historian, I am not proficient in cuneiform. I will have to rely on transliterations and translations. This is an issue because the primary sources that I am working with are cuneiform tablets composed in Akkadian, approximately 1350 BCE. For example, the KAR 220 tablet was initially transliterated into German (1910), later translated into English, (1960) and then transliterated again 60 years later (into English, 2020). As such, the ideas presented on the tablet have been touched by at least three people attempting to make meaning. The most recent English transliteration has taken into consideration its forerunners as well as nearly 100 years of Assyriological scholarship.

Application

In terms of working with translations of texts and the noted secondary sources, I have explained above that I align myself with communications researcher Raign.

Although none of these translations was published in a critical edition, each was translated by an expert and published in a scholarly book, journal, or corpus. My choice of translation does not eliminate the potential for varying or incorrect translations. However, the benefits of analyzing the rich trove of recovered texts outweighs concerns regarding the particular translations themselves.[11]

As such, I believe that the translations I am working with are sound, though not entirely unproblematic.

Final Comment

Other studies that have addressed Tapputi have also utilized these same tablets to provide context about her perfume-making process, specifically (see Halton and Svärd).[12] This current study attempts to create a fuller portrait of this individual as a woman and perfumer. Taken together, these sources can provide a potential portrait of a female perfumer at work during the Middle Assyrian period.